The scene was striking, sharply edited and hurtling along almost faster than a zipping stream of spider silk.

A group of robbers clean out a New York bank and run to the roof of the building to flee in a helicopter. They laugh and describe their successful heist with the old cliche of "taking candy from a baby." Lifting off, the thieves laugh more and think they will get away.

That is, until their chopper is slammed to a complete stop, causing them to nearly lose control. Panicking, the machine is hurtled backward, until it becomes tangled in a massive spider web. In a series of quick jump cuts, with the camera zooming out, the helicopter entangled in the web is suspended between the World Trade Center towers. Spider-Man has caught some thieves "just like flies," just as his 1960s theme song states.

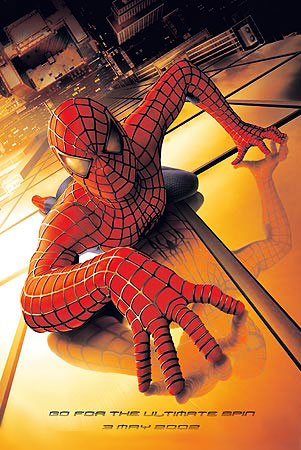

The original Spider-Man teaser poster had the Twin Towers in Spidey's eye... |

...but a replacement came out quickly after 9-11. |

This trailer for Columbia Pictures' Spider-Man, a May 2002 release, was quickly yanked off the Internet and from theaters after 11 September 2001. A related poster, in which the WTC could be faintly seen in the web slinger's eye, also was retired.

The actions of Sony Corp., Columbia's parent, were typical of studios' oversensitivity and anxiety following the terrorist assaults. A surge of fear of alienating movie-goers appeared, with movies being rescheduled or even canceled altogether. Movies with a New York locale particularly received the magnifying glass. Some had surgery performed, in some cases, with the WTC either being digitally erased from Manhattan establishing shots, to being tossed to the cutting room floor.

For some witnesses to the World Trade Center and Pentagon devastation, 9-11 looked like a horrid, real-life movie, and this comparison was widely voiced.

Wrote David Von Drehle in The Washington Post, "Bin Laden is, in one sense, the sort of menace-without-a-country that figured, cartoonishly, in old James Bond movies. If he was, in fact, the author of the attack, he has a deeply cinematic imagination. Images wrought by the attack in New York were right out of a big-budget Hollywood production, and made the realty almost impossible to believe."

Entertainment Weekly journalist Ty Burr personally witnessed the WTC's demise and caught himself reacting cinematically -- for a second. "As I watched the immediate aftermath of the collapse of the World Trade Center towers -- the rush of the cloud of debris through the canyons of lower Manhattan, the crowds of terrified people racing to stay ahead of it -- the movie Independence Day jumped to my mind. For about a second. Then that brief, glib association was completely outstripped by unforgiving reality. This was not a movie."

New York City may have been damaged in the past by meteorites, giant lizards and fictional terrorists, but all that was visual and special effects and actors and stuntpeople. Viewers could walk away and forget, because it was a movie. But with a real act of massive violence, what were Hollywood and its customers to do?

Some people thought 9-11 would change business in Hollywood, but many others thought it would hardly alter American popular culture.

Theresa Wilts of The Post wrote: "Even a national tragedy of cataclysmic proportions can alter our cultural DNA only so much. Popular culture reflects the basic id or impulses of the nation, and it's a huge business. Therefore it can be changed only so much."

Theater attendance dipped substantially after the attacks for a couple weeks but began to rebound. In fact, 2001 would substantially outdo 2000, with $8.5 billion at the box office, up from $7.7 billion.

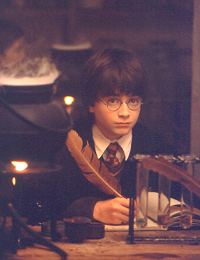

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone, the wizard fantasy with Daniel Radcliffe (above) as the title character, was #1 in box office in 2001 |

The strongest performers were comedies, fantasy fare and action movies with no reference to terrorism. Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone was 2001's top grosser, at $267.8 million. The other top films were the cartoon Shrek, $267.7 million; the actioner Rush Hour 2, at $226 million; another animated feature, Monsters, Inc., at $220 million; and The Mummy Returns, at $202 million. Other winners were the movie version of J.R.R Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, and Training Day, a raw police drama set in Los Angeles, also was a winner.

Said Paul Dergarabedian, of the firm Exhibitor Relations, "People stayed close to home, and movies were an entertainment option close to home that were relatively inexpensive. ... On top of that, there were some pretty good movies, or at least movies with popular appeal."

Hollywood was fast in changing its product and public relations after 9-11. The studios' and celebs' philanthropic sides appeared, with $10 million for victims from AOL Time Warner, and $1 million each from Rosie O'Donnell's and Disney CEO Michael Eisner's foundations.

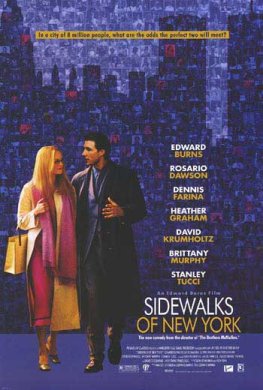

Sidewalks of New York had its release date pushed back -- and its poster converted as it went to video and DVD |

|

Among the examples of gear-shifting in product after 11 September:

In general, the release schedule was rapidly rejiggered, as romantic films, comedies, fantasies and war flicks were pulled forward, and movies with any remote connection to 11 September themes were banished to 2002.

Way too oversensitive? Some moviegoers wanted to see the World Trade Center remain in movies; it seemed to be catharsis and commemoration at the same time. Entertainment Weekly reported in October 2001 that people in a Manhattan movie house cheered when they spotted the towers in a preview clip.

Fantasy and romance may have ruled because of Americans' emotional uncertainty. Their lives already were in flux due to the times in which they lived. Richard Thompson, popular culture professor at Syracuse University, New York, said: "So many of the traditional ways of finding our future don't exist anymore. Americans change jobs seven or eight times in their lives. The idea of settling down in the town you grew up in and marrying your high-school sweetheart is quaint. So most people looking for love are, essentially, relying on the comforts of strangers."

Laurent Firode, director of a French flight of fancy called Happenstance, believed that escape was one way people dealt with 9-11's non-fiction violence. "After a major catastrophe, one sees resonance wherever one can. I'd say that right now there's a much greater need for irrational thought, like religion or astrology or simply a belief in the goodwill of fate."

Some fantasies, dramas and flag-waving flicks, though, stalled out. The Last Castle, with Robert Redford in a military prison struggle against a corrupt warden, faltered. Life as a House, an emotional, domestic drama with Kevin Kline, barely registered. What mattered was a fantasy or love story with which viewers could connect and follow an engaging plot.

Another route of coping appeared to be to still watch and enjoy action-filled, violent movies, but those not directly related to the attacks of 11 September.

Action movies that were released on schedule were those deemed remote enough from 9-11, such as Training Day, with Ethan Hawke and Oscar winner Denzel Washington. The movie almost was pulled, but Warner Bros. decided to leave it in release in September 2001. Day was set in Los Angeles and featured Hawke's frightening indoctrination into Washington's world as an undercover narcotics investigator. It was violent, but it focused upon big city street crime, not terrorism. Spy Game, with Robert Redford and Brad Pitt as CIA agents, stayed on the slate for Thanksgiving, despite being set in Afghansistan in some scenes. These sequences took place during the Soviet occupation in the 1980s.

Other action titles that were untouched were Don't Say a Word, with Michael Douglas enduring a frightening kidnapping of his daughter, and From Hell, Allen and Albert Hughes' retelling of the Jack the Ripper murders in Victorian London.

War movies, more realistic since the success of Saving Private Ryan (1998), were violent, but studios justified their early releases because of their patriotism and parallel to the real war in Afghanistan. Among the martial films moved up were Black Hawk Down, about the ill-fated battle in Mogadishu, Somalia in 1993; Behind Enemy Lines, with Owen Wilson as a soldier trapped in enemy territory in Serbia in the 1990s; Hart's War, set in a World War II prison camp; and We Were Soldiers, based on a real Army unit's bravery in Vietnam while under siege by the Viet Cong.

Some movies released in theaters before 11 September, and on DVD and video after the attacks, were downright eerie in their pop culture references. In Don't Say a Word, the phrase "ground zero" is heard repeatedly. In the science fiction fantasy A.I.: Artificial Intelligence, androids Haley Joel Osment and Jude Law fly to a New York City mostly underwater from melted polar ice caps. As their "amphibicopter" approaches Manhattan, the computer guidance system shows an navigation image with only the Statue of Liberty's hand and torch ... and outlines of the submerged World Trade Center towers. The image then dissolves to the "real thing."

The same could be said for movies that either included the WTC in footage or as a plot device since a big gorilla scaled the Twin Towers with Jessica Lange in the 1976 remake of King Kong. The buildings could be seen in everything from the opening credits of Wall Street (1987), to a site of production numbers in Godspell (1973) The Wiz (1978), to a vantage point for Macaulay Calkin in Home Alone 2: Lost in New York (1992).

As life struggled toward some semblance of "normal" in the US after 9-11, the portrayal of violence remained a major issue to film execs. How it would be shown on screens, if at all?

Terry George, screenwriter of the reshuffled Collateral Damage, predicted in The Street, "I think that some of it is surreal, almost comic book, while other movies use violence to enhance the reality. So I think, given that distinction, [people making films] with reality-based violence will become more cautious.

"I think one of the major problems that the movie industry now faces -- particularly the big studios that produce the mega-blockbusters -- is that the reality of events on Sept. 11 so overshadowed and engaged and shocked this nation and the world, that any attempt to come close to, or duplicate, or re-enact a similar scenario is going to look pretty foolish and pathetic."

Stephen Holden, a New York Times movie critic, agreed that violence would not be completely shelved. What would matter was the way it was portrayed and the context.

"Right after [9-11], Training Day, which is a very violent movie opened and did fabulous business," Holden told PBS's NewsHour in January 2002. "So no one was averse to watching violence on the screen. I do think that we're going to have more heroism in films, that people ... films will be less ... a little less cynical than they were. I think that what this whole series of events has done is bring back a real belief in heroes, because we've seen real heroes. And that's going to impact a lot of mainstream films."

Violence was indeed to stay in movies, but more of a comic book style, as literally in the Spider-Man adaptation, and in movies with a similar flavor, such as the Vin Diesel "extreme" secret agent flick XXX or the 20th James Bond movie, Die Another Day.

Only weeks after 11 September, rentals of action-adventure movies actually increased. Video stores saw higher checkout rates for Die Hard (1988), Independence Day (1996) and other films with explosions or fiery disaster.

Some people speculated if Hollywood's push for a global market and boldness to show violence and terrorism before 9-11 could have influenced USA detractors to reenact such incidents.

There have been movies with plots touching upon 9-11 -- Turbulence (1997) had an American villain playing cat and mouse with a flight attendance on an out-of-control jet that threatens to hit Los Angeles buildings. The Siege (1999) had Middle Eastern terrorists leveling a federal building -- in New York -- with a bomb. The result is martial law by a general (Bruce Willis) and internment camps for Arab and Muslim men. And in the first two Die Hard movies, Bruce Willis first must battle terrorists who want to detonate an L.A. skyscraper, and second some South American ones threatening to blow up a jet.

George did not hold Hollywood responsible for inspiring terrorists. "What was discussed [at a late 2001 roundtable with military officials] was that we now very clearly live in a global market. There's been a level of cultural globalization that Hollywood writers, for television and for screen, have to become acutely aware of, because clearly the message from the Islamic world is that some of the culture that emanates from Hollywood and the United States deeply offends a section of their population."

There was a reason for violence, studio executives would say before 9-11. Action-adventure films brought in the viewers, and handsome profits were made. Movies are a business, after all. Men like Schwarzenegger, Willis and Sylvester Stallone became multi-million dollar stars due to such movies, with their hyper-realistic visual and special effects.

Images like the classic alien destruction of the White House in Independence Day were placed without hesitation in movies before 9-11. |

Richard von Busack, a San Francisco Bay Area journalist, wrote that action movies shifted from refined, intelligent James Bond villains to the violent acts themselves being the stars. For example, audiences ate up imagery, such as aliens zapping the White House into oblivion in Independence Day, or the repeated fantasy abuse in the '90s of New York's Chrysler Building, because they were humbling to the United States' seats of political and financial power.

"In these explosion scenes," von Busack said, "you got the best applause when the buildings were in D.C. and New York: we know that the terrorists, aliens or meteors were punishing New York arrogance and Washington weaselry. The very size of the destruction meant that no hero -- not even Superman -- could be equal to the effect; the blown-up buildings were the stars of the show."

Hollywood fare may have not changed substantially, but some aspects of movie denizens' lives did. The Golden Globes and Academy Awards had extremely tight security. It was so intense that a Polish man who had won an Oscar for Best Documentary, who went outside the Kodak Theatre for a cigarette, was barred from going back inside, even after insisting he was an award winner.

Celebrities at the Golden Globes in January 2002 reflected that life had to move on. "It's like the 16th century with the plague. You accept that you're living with something dangerous, but you make the moments count," said Australian Baz Luhrmann, director of Moulin Rouge (2001).

Actor Michael Caine, a presenter, said, "I'm from England. We've been doing this for years. Better to do this than get blown up, don't you think?"

Filmmakers and critics interviewed at the Sundance Festival in Park City, Utah, in February 2002 believed that Hollywood would revert quickly to old behaviors. Escapist movies would top their product line, and political movies, which did well in the 1960s and '70s, would be unpalatable.

"Will Hollywood change? No, it won't," said Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun-Times critic. "Moviegoers cheerfully go to trash, knowing that it's trash. Audiences are depressingly incurious about good movies."

Critic Amy Taubin added, "We go to movies to take our minds off of whatever's going on out there in the world. Film is a distraction. It's troubling."

Action and fantasy continued into 2002, along with the endless ailment called "sequel-itis." Among those franchises or characters with new installments that year were Harry Potter, Austin Powers, Spy Kids, The Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, Rush Hour and Men in Black. In others, nearly business as usual.

The prediction of Entertainment Weekly's Ty Burr was somewhat correct: "Seriously, would you ever, EVER want to watch things blow up for the fun of it again? I wouldn't, but maybe you would. And, to a degree, this will all pass. The new TV shows will debut, movies will be released, the machinery will once again crank up. Many in the audience will be relieved, others will find it vaguely ridiculous."

Even 9-11 itself may not remain very long before the movie industry decides to make some kind of film about the day. While the first "Day of Infamy," Pearl Harbor, did not appear on screen until 29 years later (Tora! Tora! Tora! in 1970), Hollywood may not wait for 9-11 to pass that deeply into history.

Variety, the venerable showbiz paper, stated that studios were being pitched with three magazine articles that appeared after the attacks. Two were about John O'Neill, a counter-terrorism expert who ironically was killed in the WTC attack. The third was about a fireman who was pulled from the Twin Towers rubble and was suffering from amnesia.

"Pearl Harbor, which was a day that shall live in infamy, became a Michael Bay movie," said Edward Zwick, director of The Siege. "Titanic was the greatest tragedy ever to hit the country, and that became a movie. It's all about time and distance. Never say never."

The big screen's home-based counterpart, television, already did address 9-11 in fall 2001. There was an episode on terrorism on The West Wing, and Third Watch, a drama about New York firefighters and police officers, wove the WTC assault into its plotlines. CBS News aired the documentary 9/11 six months after the attacks. This film had extensive footage with anxious firefighters inside 1 World Trade Center and the disturbing sound of bodies hitting the plaza outside.

| SCREENSHOTS FROM THE PULLED SPIDER-MAN TRAILER | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TO GALLERY: PERSISTENCE OF VISION -- 25 YEARS OF WTC MOVIE IMAGERY >>

TO GALLERY: PERSISTENCE OF VISION -- 25 YEARS OF WTC MOVIE IMAGERY >>

Home | About This Site | The Basics | Article Index

E-mail the Webmaster