After an assignment in the Dominican Republic, news photographer Thomas E. Franklin was back to his usual territory, the New York-New Jersey area.

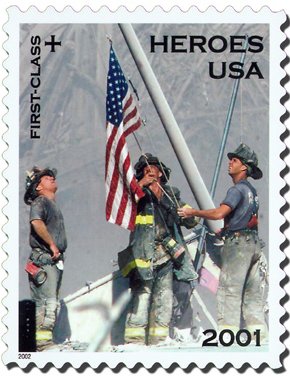

The US stamp version of Franklin's famous image (USPS image) |

His day began at 8 a.m. 11 September 2001 at the offices of his employer, The Bergen Record of Passaic, New Jersey. An editor told him a plane hit the World Trade Center. Franklin, who had been on the paper's staff since 1993, headed down the New Jersey Turnpike to Jersey City. He heard about the crash of United Flight 175 into the WTC south tower on the radio.

Franklin stopped at Exchange Place in Jersey City and went to the riverfront. As a veteran of the news coverage area, he knew where the best views of the WTC would be. He put a memory card into his digital camera. He witnessed ferries carrying wounded persons and the establishment of a triage area and took shots of the action.

"The whole day was an emotional roller coaster. I was scanning the faces in Jersey City, hoping that I would see my brother. He works two blocks south of the World Trade Center. I didn't find out until 3 o'clock that afternoon that he was okay," Franklin recalled in The Record.

By noon the ferries began to taper off. Another photographer, John Wheeler, convinced the police to let himself and Franklin take a tugboat to New York. He first arrived at WTC 7, a 47-story structure that would collapse that night. As Franklin further penetrated Ground Zero, police threatened to arrest him about a half dozen times.

Franklin was traveling with James Nachtwey, a Pulitzer-prize winning photojournalist who told him he had just narrowly escaped death at Ground Zero.

Around 4 or 5 p.m., Franklin and Nachtwey were taking a break and drinking water and juice. A trio of firefighters caught his eye.

"I would I say was 150 yards away when I saw the firefighters raising the flag. They were standing on a structure about 20 feet above the ground. This was a long lens picture: there was about 100 yards between the foreground and background, and the long lens would capture the enormity of the rubble behind them," Franklin said.

The three firefighters, William Eisengrein, George Johnson and Daniel McWilliams, had discovered a US flag on the back of a yacht inside a boat slip at the World Financial Center. They took the banner and decided to raise it as a statement of loyalty and resilience.

Franklin recalled, "I made the picture standing underneath what may have been one of the elevated walkways, possibly the one that had connected the World Trade plaza and the World Financial Center. As soon as I shot it, I realized the similarity to the famous image of the Marines raising the flag at Iwo Jima.

"This was an important shot. It told more than just death and destruction. It said something to me about the strength of the American people and of thse firemen having to battle the unimaginable."

Two generations ago, when the US was in World War II, Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal snapped a picture of six Marines raising Old Glory on Mount Suribachi on the Pacific island in February 1945. The photo became a WWII icon and the basis for a Marine Corps memorial sculpture in Washington, D.C. The Battle of Iwo Jima also is recognized as the beginning of the end of the campaign against the Japanese in the Pacific.

The firefighters of Engine 255 and Ladder 157 of Brooklyn had been digging in the rubble and searching for survivors at WTC 7, when they were told to evacuate. The weakened structure was close to collapse.

During the evacuation, McWilliams, 35, of Long Island, saw the yacht, Star of America, owned by Shirley Dreifus of the Majestic Star company in New York. He took the flag and its pole from the stern and rolled it up so it would not touch the ground. He took it to the evacuation area. The Old Glory itself was American made, originating from Eder Flag Manufacturing of Oakcreek, Wisconsin.

McWilliams, of Ladder 157, passed a coworker, Johnson, 36, of Rockaway Beach, Queens. He slapped Johnson on the shoulder and said, "Give me a hand, will ya, George?"

Eisengrein, of Rescue 2 from Brooklyn, saw them and said, "You need a hand?" Eisengren also was a childhood friend of McWilliams on Staten Island and still resided there.

The firefighters found a flagpole within rubble about 20 feet off the ground on West Street. They used a improvised ramp to climb to the pole to raise the flag. As they performed their act, Franklin aimed his long lens in their direction.

McWilliams remembered that other fire personnel yelled, "Good job!" and "Way to go!"

"Ever pair of eyes that saw that flag got a little brighter," McWilliams said.

The three firemen decided to raise the flag on the spur of the moment. McWilliams said that "a big part of this is maintaining the unity of the whole team." The men were stressed from the WTC collapse and the lack of survivors among the debris.

"Everybody just needed a shot in the arm," McWilliams told the Associated Press.

In all, 343 firefighters died in the Trade Center disaster, along with 23 New York City and 37 Port Authority police officers and six medical rescue workers.

Franklin's photograph appeared in the 12 September 2001 Record. Reaction was swift and emotional. The flag raising firemen were hit with numerous calls from friends and family. Their first reaction -- surprise, as they didn't know Franklin took their picture.

The Record itself received 30,000 requests to reprint the photograph, which the paper initially granted if they were not for profit. Among the requests from commercial concerns were to reprint it on shirts and three-dimensional music boxes.

The periodical stopped the gratis distribution and instead asked for donations to its disaster fund, which eventually swelled to $400,000. The money was distributed to charities selected by McWilliams, Johnson and Eisengrein. The photo eventually was made into an authorized poster sold through the paper's Web site and private companies.

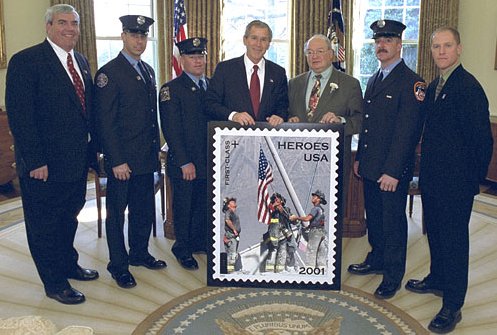

Firefighters and photographer are reunited at the stamp unveiling on 11 March 2002, six months after the Trade Center attack. Standing (from left) are Postmaster General Jack Potter, Firefighters William "Billy" Eisengrein and George Johnson, President George W. Bush, US Rep. Gary Ackerman (D-N.Y.), Firefighter Dan McWilliams, and Thomas E. Franklin. (White House photo) |

Slight variations and outright replicas began to appear across the US in fall 2001: a New Orleans prison bore a mural of the image, and copies of it were left as "calling cards" by troops in Afghanistan. At Thanksgiving 2001, Franklin himself saw a two-story replica on the side of a building on FDR Drive in New York.

Firefighters with flags began to appear in paintings and drawings, and on pins, buttons, T-shirts, hats and Christmas ornaments. Taverns, hair salons and offices hung the picture. Phoenix, Arizona, firefighters reenacted the scene before the start of Game 1 of the World Series featuring the Diamondbacks and New York Yankees. Through Associated Press distribution, the Franklin photo was used by many magazines and papers.

"The photo is taped to the wall at Attitude, a hair salon in Austin, Texas. A bartender at Sparky's Sports Bar & Grill in Sparks, Nev., wears a T-shirt with the photo most nights. The Daily Ardmoreite in Ardmore, Okla., uses the photo every day on its front page as a graphic to accompany the top terrorism story," a December 2001 AP story relates.

"David Gittings, a sewer inspector in Louisville, Ky., cut the photo out of a newspaper and has it framed on a living room wall. 'That was a signal to bring everybody together,' he said. 'You can kick us, you can hit us, but we're not down.' "

At the end of 2001, the Associated Press Managing Editors Association and Editor & Publisher magazine named it the best picture of the year. The photo was on the short list of photographs considered for the Pulitzer Prize.

The use of the firefighter photo for profit became so rampant that by December 2001, the flag trio and The Record finally hired the New York law firm of McCarthy & Kelly to protect the paper's copyright and block unauthorized uses for commercial purposes.

"While most claim to be donating all or part of the proceeds to the World Trade Center disaster charity funds, we are not confident that the revenue generated by the sale of these illegal products is actually finding a way to the families that have suffered," partner Bill Kelly said in a statement.

One revenue generating venture was approved -- a "Heroes 2001" stamp issued by the US Postal Service with the Franklin image. President George W. Bush, as part of the six-month remembrance rituals of 11 March 2002, unveiled the stamp in the Oval Office. Franklin, Johnson, Eisengrein and McWilliams attended the ceremony.

The stamps had a plus sign instead of a price. They cost 45 cents rather than the usual 34-cent first class price. The extra revenue was to go the Federal Emergency Management Agency; a little paid for Postal Service operating costs.

One replica of the photo even generated controversy. In December 2001, the New York Fire Department unveiled a study of a memorial statue based on the picture, but with the firefighers as black, Latino and white. The three original men are all Caucasian. The sculpture was by StudioEis of Brooklyn.

"Given that those who died were of all races and all ethnicities and that the statue was to be symbolic of those sacrifices, ultimately a decision was made to honor no one in particular, but everyone who made the supreme sacrifice," said Frank Gribbon, an FDNY spokesman.

Many of the complaints about the statue came from New York firefighters themselves. They criticized their department for being politically correct and "rewriting history," as the father of fireman Thomas Casoria, a WTC victim, said.

The statue was supposed to be installed by spring 2002 at FDNY headquarters in Brooklyn. The $180,000 costs were to be covered by the property management company that owned the headquarters site. After the complaints the fire department went back to the drawing board for another attempt at a memorial.

Franklin remains modest about the picture, saying that it was only chance he witnessed the firefighters. The only reason the photo was printed in The Record was because Franklin got a police boat ride to Liberty State Park; a hitchhiked ride to his car in Jersey City; and the use of facilities at a hotel to transport it after he could not get around a roadblock.

"In the back of our minds, all photographers believe we're going to get 'the big one.' I've shot hurricanes (and) earthquakes. But I've never seen anything like this," Franklin aid. "There were times during the day that I cried. Nothing had ever touched me as emotionally as this. But I had a job to do ... Once I made deadline, all I wanted to do was see my wife and my son."

More information:

The Record (New Jersey)

Ground Zero Spirit

Home | About This Site | Article Index

E-mail the Webmaster