|

|

That is a question with many answers. ArtLex, a dictionary of the arts, gives this good, overall definition: "Low (as opposed to high) culture, parts of which are known as kitsch and camp. With the increasing economic power of the middle- and lower-income populace since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the nineteenth century, artists created various new diversions to answer the needs of these groups."

Popular or "pop" culture is products produced and sold to the general public, which over time become artifacts of a distinct point in history. It is movies, television, periodicals (newspapers, magazines), books, videogames and CD-ROMS, the World Wide Web, cartoons, comic strips and books, paper goods, (posters, postcards), mass fashion, fads, housewares and decorative arts.

Pop culture is fictional or real-life characters or entities, both beloved and reprehensible, widely known or given "cult" status; to wit: Mickey Mouse, Elvis Presley, Austin Powers, Betty Boop, Scooby-Doo, Our Gang (aka Little Rascals), Snoopy, Superman, Richard Nixon, Powerpuff Girls, the Six Million Dollar Man, Freddy Krueger, Dr. Who, Speed Racer.

Pop culture represents both perennial characters and plots and forgotten fads. The aforementioned Mickey Mouse, for instance, first appeared in 1928 and is still going strong as a character and source of profit for the Disney Co. How Mickey Mouse or Superman, for that matter, have change in the decades since their entry into pop culture could be a topic of study.

Some pop culture hits a feverish fad period, settles down, and then never goes away. An example is the fights that broke out in stores at Christmas 1983 over Colleco Industries' Cabbage Patch Kids. The demand died out, but the dolls are still made and sold to this day, now by Mattel.

Some pop culture is related to a specific timeframe, either because it evolved then or was produced in response to historic events. An example of time-specific pop culture that is strongly associated with an historic period is disco, which enjoyed popularity circa 1975 to 1980. While disco has been revived on CD compilations, movie soundtracks or a plot device, it has not widely been revived as a full-blown lifestyle with fashion, lingo and music.

Often artifacts that respond to major historic events are freighted with whatever emotions, ideologies and passions people felt as they reacted to the event(s). Even more so, take the event that brought the United States into World War II -- Pearl Harbor. A government poster showing a tattered flag and an admonition to "never forget" carries the emotion of the wounded, shocked nation. Later, as WWII was the backdrop of life from 1942-45, a movie like They Were Expendable or a song like "Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy" can be viewed as still other pop culture artifacts, specifically related to their point in time. And that is what 9-11 pop culture will be considered in this study.

The historic United States date 11 September 2001 has acquired a body of popular culture of its own. From documentaries to tribute concerts to posters and digital art, the "Second Day of Infamy" has a rich outgrowth of the day's terrible attacks from which we can learn of early 21st century life and how we Americans in those days coped with crisis.

Though it may sound tacky to say tragedy has "pop culture," this is not saying that the sad event itself is pop culture, only that it has spawned a body of pop culture. In fact, it is now inevitable, considering the patterns of history from the 19th to the 21st centuries. Take a still discussed and dramatized incident 89 years before the World Trade Center and Pentagon attacks -- the RMS Titanic and the iceberg on 15 April 1912. After the great White Star Line ship sank, there followed sheet music, books, ceramics, silent film recreations on down to James Cameron's 1997 epic. The songs of 1912, such as "It Was a Sad Day When the Great Ship Went Down," and "Down With the Old Canoe" (sung for years at summer camps) could be compared to those of 2001, such as "Let's Roll" (Neil Young) or "No Sure Way" (Loudon Wainwright III).

As the Internet contains hundreds of memorial and historical sites on 9-11, and only a handful that examine its resulting pop culture, I decided a study of these artifacts would be interesting and perhaps needed.

As I am a journalist and researcher, and not a historian, sociologist or other academic, I perhaps have stretched the definitions of pop culture on this site. In creating the site, I have decided to classify 9-11 popular culture in two broad catergories: 1. organizational-professional; and 2. amateur-homegrown.

Organizational-professional is any popular culture artifacts produced by commercial corporations or conglomerates or non-profit and philanthropic organizations. An example might be the fall 2001 Alan Jackson song, "Where Were You (When the World Stopped Turning)," written and recorded by the country singer for his album Drive, issued by Arista Records. Another would be 9/11, a documentary about New York firefighters dealing with the World Trade Center crises, by the brothers Jules and Gedeon Naudet, aired on CBS-TV.

Amateur-homegrown pop culture grew out of the increasing availability of technology to the citizenry, such as graphic editing software and MP3 digital compression technology. Examples are patriotic and anti-Osama bin Laden graphics in JPEG or GIF format for display on the Web; MP3 recordings of memorial or parody songs by unsigned bands; and Macromedia Flash movies showing 9-11 victims and imagery while set to sad or reflective music. For lack of a better term for these items, they also could be labeled 9-11 "folk art" due to often being produced by individuals or small groups possessing varying degrees of professional skills.

The focus of the bulk of my research and analysis was on popular culture artifacts produced between 11 September 2001 and March 2002. The first six months were especially a time of dramatic events and high emotion. The fact that the nation needed to mark a six month anniversary, as opposed to waiting an entire year, seemed to make a good ending demarcation. Some artifacts are included from before 9-11, as these items contributed to the evolution of those that followed. For example, to consider the World Trade Center as popular culture artifact and icon, the complex's history and past representations must be reviewed over its 30 years of existence.

Pop culture artifact classifications used are 1. traditional paper (books, calendars, posters, magazines); 2. electronic media/permanent storage (DVDs, videotapes, CD-ROMS, videogames); and 3. electronic media/display, meaning that the item in its original form was an image or moving picture on a computer screen (JPEG image, MPEG video).

Much of 9-11 popular culture is a vehicle of emotions and outgrowth of people needing to express themselves. Feelings were complex and potent in the September 2001-March 2002 timeframe: rage, grief, shock, trauma, disbelief, revenge, nostalgia, remembrance, high patriotism and later, even humor and satire (as directed at enemies). Even commercially produced items represent some feeling, because the desire to make money is an emotion, too, if you think about it.

The 11 September materials also were produced in many cases to comfort or reassure Americans thrown into uncertainty after only the third attack on their own soil in 225 years of existence. Finally, some of the items were more callously marketed to make money off wounded people ... the worst reason to make pop culture items, but one that did exist.

I further used the concept of traditional paper ephemera, or materials designed for brief consumption (e.g. a calendar or postcard) and digital ephemera. Both types of ephemera are explained in detail on another page.

Research for 11 September popular culture was conducted both through traditional and new media. This project's inception was in fall 2001, as I gathered items, and this actual Web site commenced on 18 March 2002, six months and one week after the attacks. The World Wide Web was vastly invaluable for discovering artifacts and primary sources (mass media materials produced at the time of the attacks). Primary sources were vital in order to understand the sentiments of the timeframe, of how people already were trying to analyze the impact of the attacks on aspects of popular culture.

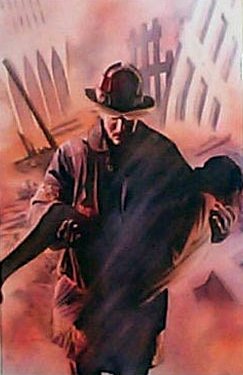

Alex Ross' cover art for the Heroes Among Us exhibit by the New York Comic Book Museum and New York City Fire Museum, 22 January-7 February 2002. (From the NYC Comic Book Museum) |

The Internet was a treasure trove of both the professional-organizational and amateur-homegrown items, as well as dozens of articles discussing and dissecting pop culture at the turn of the 21st century. September 11 was the first major historic event of the Internet era, and the Web rose to the occasion to document and remember it. I was able to reproduce numerous artifacts for presentation in a digital form on this site, thanks to the searching and classification powers of the Net.

My first step was to dig into books and periodicals for social and historic background on items as varied as modernism and popular culture, symbolism, patriotism, historic events of year 2001, and the World Trade Center.

Second, artifact research involved experiencing the popular culture, such as looking at digital Web art of a crying eagle, buying and inspecting a poster of the Twin Towers with a flag in the background, listening to Young's song "Let's Roll," viewing a documentary, or sitting through The Concert for New York City.

Based on the knowledge acquired about 9-11 through reading, research and personal experience (I was 39 when the attacks occurred and saw much of the news coverage first-hand, as did millions), I offer some analysis and opinion of how and why the pop culture artifacts were produced. Also included are quotations and comments of artifact creators themselves addressing the origin or rationale for their contributions.

The approach is from the general to the specific. Individual avenues of popular culture, such as movies and music, are discussed in articles. Other stories address the origins and tales behind specific examples or icons, such as Thomas E. Franklin's firefighters and flag photo, the WTC and phony e-mails.

This is an ongoing project, as material is constantly discovered and requires review. The body of 9-11 popular culture and the avenues of delivery are great, due to the technology of this point in time.

Design of the Web site has deliberately been kept simple, because the focus is on the content. Anyway, I am a writer, not a professional designer, and my best Web language is HTML, with a smattering of JavaScript and Cascading Style Sheets. I also have limited skills on Paint Shop Pro, enough to present graphic support for the articles posted on the site. And always, your comments, critiques and suggestions are welcome. An e-mail link is at the bottom of every page.

--Victoria Mielke, Webmaster

NOTE: A number of items on these pages are copyrighted materials. This is a nonprofit research site with no commercial intent. Any copyright-affected items are displayed for illustrative purposes only as a supplement to the text.

Related:About the Webmaster and personal reasons why I created this site.

Related:About the Webmaster and personal reasons why I created this site.

Home | About This Site | The Basics | Article Index

E-mail the Webmaster